To many, the formula for great comedy is simple - have a stupid character do something stupid.

But stupidity is not the key to funny. A comedy character must engage the viewer before he can make them laugh and, to put it simply, an imbecile is not engaging.

Who can root for a character too dumb to ever do anything right and so lacking in grey matter that he can never extract himself from trouble? The fool will eventually step off a cliff, never to be heard from again. What is the point of caring for an individual who we know from the start is doomed?

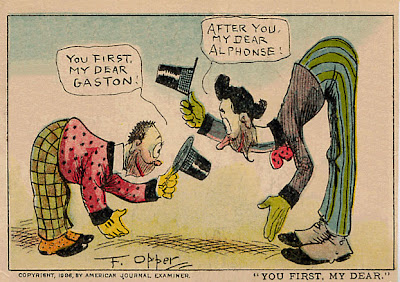

![]()

The three biggest comedians of silent films, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, made a point to play intelligent, resourceful characters. Audiences responded favorably to these characters, finding it easy to identify with them and care about them. According to the song "Make 'em Laugh," all that a comedian needs to do to get a laugh is to "Take a fall, but a wall, split a seam." That may work for five minutes, but these comedians were required to carry features that were an hour or more in length. Their actions had to advance a story and demonstrate character development. In the end, these characters had to be able to make timely decisions to overcome obstacles and achieve goals. Aristotle believed that we laugh at inferior individuals because we derive enjoyment from feeling superior to others, but the ancient philosopher would likely have had a different opinion if he'd been able to see

Our Hospitality (1923) and witnessed how resourceful Keaton could be in eluding determined assassins and stopping his lady love from toppling over a waterfall.

Intelligence never provided Chaplin, Keaton or Lloyd with immunity from comical adversity. Their smart characters were challenged by difficult circumstances. Their smart characters often had to struggle within themselves against a simple human emotion or an unfortunate character flaw. Lloyd's conflicts were often internalized in this way. He must prevail over his bashfulness in

Girl Shy (1924) and he must prove his manhood in

The Kid Brother (1927).

Intelligence furnishes a person with a variety of abilities: learning, reasoning, planning, and problem solving. Still, the process of learning, reasoning, planning and problem solving is not always straightforward. Intelligent thought can be sidetracked by many of our faults. Cowardice. Vanity. Lust. Greed. Shame. These qualities and others can make reasonably intelligent people make foolish decisions. But these problems are more complex and profound than the problems of an idiot. This is the reason that it is much harder to write for a comedy character with intelligence. Tina Fey said that having her do dumb things on

30 Rock could be funny, but she admitted that the writers found these situations easy to create and went to them far too often.

Of course, some fools are exceptions, being able to endure the inevitable tumble off a cliff. I mean this both figuratively and literally. Think of Larry Semon, a cartoonish dolt who could be expected to hit the ground and astoundingly bounce back up to the brink of the cliff, or Harry Langdon, a divinely protected innocent who would in all likelihood drop safely atop a hay wagon. But Semon and Langdon, despite their many talents, were limited in their range and their appeal.

This is a fool protected by the fates.

Here is just a fool.

This is not to say that Keaton, as smart as he was, never benefited from good fortune. This is evident in the following scene from

Our Hospitality.

But, whenever in possession of the facts, Keaton was often able to work out astonishing solutions to problems.

The smart comedian could always introduce an inebriation scenario if they ever wanted to indulge in stupid behavior. See Charlie Chaplin in

One A.M. (1916) or Charley Chase in

Bromo and Juliet (1926).

It helps when discussing the intelligence level of a comic hero to take a look at Gomer Pyle. Pyle started out on

The Andy Griffith Show as a slack-jawed dimwit. Even though he worked in a gas station, he didn't know a carburetor from a hood ornament. This is made evident in the

Griffith episode "The Great Filling Station Robbery" (1963).

Sixties sitcoms depended so much on misunderstandings that few characters in these series were good at discerning circumstances or communicating with one another, but these characters were not dumb either. Sixties sitcoms relied on a strict story structure. The protagonist had to start at point A, travel to point B, and end up at point C. In the process, he needed to learn something about himself and bring to light a moral message. It didn't have to be a profound message. Sufficient for the sitcom's purposes was a simple familiar American homily - "Honesty is the best policy," "Don't judge a book by its cover" or, maybe, "The grass is always greener on the other side." A character could not function in this structure without a fair amount of intelligence. You cannot find progress or meaning in the chaotic actions of an imbecile. It differs greatly from the limited Three Stooges formula:

something happens (usually something breaks), something else happens (usually someone is injured), and then the action ends abruptly (the trio run off to escape a pummeling). No plotline. No character development. No familiar American homily. The clock runs out. Have you had enough laughs? Good. The Three Stooges were more about property damage and physical injury than character development and moral lessons.

It wasn't long before the writers of the

Griffith show boosted Gomer's IQ to make the character more functional and allow him to play a larger role in the series. This is evident in a

Griffith episode called "A Date for Gomer" (1963). By now, Gomer has become a more substantial character. He is reasonable, sensitive and, most of all, sympathetic.

Gomer's IQ was further increased when the character moved into his own series. Aaron Ruben, the show's producer and creator, said, "Gomer was not at all stupid and he was not really a clumsy goof. He just did things in his own country way." Gomer, trusting and helpful, is out of place in a world filled with cynics, phonies and scammers. But that wasn't his only problem. Gomer is unaccustomed to the formal structure of the military culture, which involves manners that are not explained in a regulations manual, and he has yet to become familiarized with the marine's way of life. Gomer breaking the rules reflects badly on his military trainer, Sgt. Carter (Frank Sutton), which puts Carter at risk with his superiors.

![]()

Nothing in the series was more important than the relationship between the oddball private and his hardboiled sergeant. A 1965 article published in the Gloversville New York Leader Herald praised the team of Nabors and Sutton. The article read, "A principal reason for this season's success of Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. is the hot and cold war between Gomer and Sgt. Carter, possibly the best military feud since Quirt and Flagg of

What Price Glory. They make a prize pair — the ingenuous trouble-magnet Gomer as played by Jim Nabors and the harassed sarge, etched in slow-burn by Frank Sutton." An astute critic of the day noted that Sutton was the best comic hollerer on television since Jackie Gleason. The fact was that Sutton was now playing Ralph Kramden to Jim Nabor's Ed Norton. Of course, the point could be made that Kramden and Norton had simply been molded into a small screen version of Laurel & Hardy.

Let us look, for a moment, at Laurel & Hardy. The "Two Minds Without a Single Thought" perspective of Laurel & Hardy may be overstated. This point is well-stated by Trav S.D. in his new book,

Chain of Fools. S.D. wrote, "[I] don't buy the line that Oliver is as dumb or dumber than Stanley which many commentators (including the comedians themselves) seem to espouse. Instead, what I observe in the films is that Hardy’s character is more worldly than Stan, knows on some level how the universe operates, has a bigger vocabulary, and would probably be just fine if he wasn’t saddled with his dim-witted partner." The faithfulness and trust that Oliver Hardy maintains in his close friendship with Stan Laurel may, in fact, be his greatest weakness. In this way, Hardy suffers more from a weakness of the heart than a weakness of the brain. I leave out the team's costume comedies from this discussion as, somehow, the comedians lost any semblance of adult knowledge once they got into historical garb. Let's look at a scene from

The Bohemian Girl (1936). Hardy's wife and her dastardly lover have kidnapped a nobleman's young daughter. Hardy is understandably puzzled to see this unfamiliar little girl hanging around their camp.

Forget about copulation, conception, gestation and birth, Hardy evidently believes that babies are brought down from Heaven by a stork. The team's modern-day personas were a little wiser to "baby makes three" dynamics.

The boys later return home with a baby as if babies were something you picked up at the market. They have still skipped past copulation, conception, gestation and birth, but at least they have no illusion about storks.

Hardy's machinations, no matter how finely formulated, were bound to be undone by Laurel.

Note that, at the end of that last scene, Hardy handles an epic setback with resilience and resourcefulness.

To this day, we still find comedy situations in which a blustery man is regularly put into trouble by a nitwit friend. Take, for example, this scene from

The IT Crowd. This fool is about to be reduced to a cinder.

Of course, Stan and Ollie are exceptional in many ways. In

Way Out West (1937), the pair is determined to do whatever it takes to reclaim a deed that they were dumb enough to lose. But shining through their bungling is a sense of responsibility and a determination. These are admirable qualities that inspire faith in the dimmest of characters. Stan and Ollie never give up hope in themselves and we never give up hope in them. Besides, these fellows are so charming that they cannot help but inspire undying affection and sympathy.

Two other great comedy icons of the 1930s were W. C. Fields and Groucho Marx, both of whom played characters that were far from stupid. The intelligence level of the film comedy character went into decline in the late 1930s. You might blame The Three Stooges. You might blame Abbott & Costello. The problem was that comedy presented by these performers was not connected to a narrative. Both teams shifted their attention away from storytelling to focus instead on "the funny parts." Although Abbott & Costello headlined feature films, their characters were rarely responsible for driving forth the plot. Other characters carried the stories, leaving the pair to appear occasionally to interject an old burlesque routine. In the case of both teams, children became the most loyal and affectionate part of their fan base. Children, who are still working to attain an intelligent understanding of the world, are easily able to identify with bumblers.

![]()

We now return to the question of whether or not Gomer Pyle was a bumbler. The fact is that the early episodes of Pyle repeatedly demonstrate Gomer's sharp wits. Gomer employs a clever plan to lead his platoon to victory during maneuvers ("They Shall Not Pass," 1964), he figures out the scheme of mother-daughter con artists and finds a way to thwart the crooked pair ("The Case of the Marine Bandit," 1964), and he captures a gang of thieves ("Sergeant of the Guard," 1965). It was only on a rare occasion that

Gomer's writers went the easy route to dumb comedy.

The first season of

Pyle was marked by a humor that was quiet and natural compared to the sort of comedy that characterized the series' later seasons. An episode that very much reflected the style of the first season was "Survival of the Fattest."

But another episode, "Gomer and the Dragon Lady," was more boisterous and laugh-out-loud funny and it was this episode that established the formula that would later carry the series through its second and third seasons.

It was obvious at the start of the second season that the writers had figured to make Gomer less intelligent so that he could cause Carter greater grief. Gomer now causes major accidents. He repeatedly sinks a raft in "Gomer Captures a Submarine" (1965) and he blows up a pick-up truck with a bazooka in "Home on the Range" (1965).

Gomer's various misadventures put into question the very meaning of intelligence. The first season often showed Gomer grinning happily while Carter yelled at him. Gomer remains blissfully unaware as this other person expresses distinct displeasure towards him. He fails to grasp obvious social cues and react appropriately. Doesn't this make him somewhat of a clod? It could be argued, though, that Gomer is simply perceptive enough to see through Carter's gruff exterior and recognize his true good nature. But, now, let us consider a scene from a second season episode, "Vacation in Vegas" (1966). Gomer has won a free weekend for two in Las Vegas and has allowed Carter to join him. But he fails to grasp the simple and obvious fact that Carter would rather enjoy the town's shows, casinos and ladies than spend an afternoon visiting a rock museum.

Intelligence is a capability for comprehending people and situations — catching on, making sense of things, or figuring out what to do. Gomer has poor skills when it comes to comprehending people and situations. He never seems to be able to catch on. Here is another example.

Gomer has no idea that he is being a nuisance to the shop owner.

In "Dance, Marine, Dance" (1965), Carter tries to get Gomer out of a contract with a crooked dance school only to be conned into signing a contract himself. Trust, and possibly a bad understanding of math, is what allows Gomer to be conned into signing the contract.

But the contract pitch turns out differently with Carter, who is led astray by his lust for the alluring dance instructor and the dance instructor's appeal to his vanity.

Who, here, is more stupid? You put trust in a person only if you have reason to believe the person is worthy of trust. Otherwise, you are using poor judgment, which is plain old stupid. But keep in mind that Gomer grew up in a small town surrounded by people he could trust. People in close-knit communities find that it is vital to preserve the trust of their neighbors and safeguard their reputation. A person who wrongs a neighbor will be found out quickly and ostracized. It is better to let your word be your bond. Gomer is still in the process of learning that people in the city are less trustworthy. He may have failed to realize that the shop keeper was irritated with him because he never thought to look past the man's genial facade. Even the most intelligent person needs time to learn how to adapt to a new environment. Intelligence is, at its core, about the ability to learn and adapt. Learning would mean that Ollie can finally figure out that he needs to avoid this dip in the riverbed.

Carter perhaps comes across as less intelligent in this particular situation. True, a crucial part of intelligence is the ability to understand people, but it is even more important that a person has the ability to understand oneself. Self-awareness allows a person to recognize his own shortcomings and regulate his actions accordingly.

At first, the series relied heavily on fish-out-of-water comedy. Gomer's values, in general, do not transition well to his new environment. Gomer's kindness with animals, which may be appropriate in a rural setting, frequently gets him in trouble on the base.

Gomer's honesty turns into a vice in "Gomer the Star Witness" (1965) when Gomer is called to testify as the sole witness in Carter's auto accident case.

In the fourth season, the writers took the goofy marine into a different direction. In the process, the series introduced major changes in the situations and characters. Dr. J, a frequent contributor to Amazon's customer reviews, perfectly summarized these changes in a review of the series' fourth season DVD set. He wrote, "Gomer's and Sergeant Carter's roles in the show are quite different. In the earlier years, the show is based on Gomer antagonizing/irritating Carter. Carter would blow up and then somehow everything would work out. But in this season, Carter is to a large degree the source of his own problems. He's the one who causes the problems - not in a comic way, but by his own vices. Then Gomer, through his flawless character, saves Carter."

![]()

Prior to the fourth season, Gomer made problems wherever he went. He was, as stated before, a trouble-magnet. This season, he is sensitive, intelligent and helpful while it is Carter who acts like a complete boob. I don't know what the producers expected to get out of reversing the relationship of their lead characters. It's comparable to switching the roles of Abbott and Costello and still expecting them to be funny. At this point, Gomer is no more than a pained straight man to Carter, who has been reduced to a blustery buffoon. This is particularly apparent in the episodes "The Prize Boat," "The Recruiting Poster," "Sergeant Iago" and "Friendly Freddy, the Gentleman's Tailor."

This is not to say that Gomer hadn't demonstrated sensitivity and helpfulness in earlier seasons or that Carter had never before suffered consequences for his vices, but these aspects of their personalities were more strongly emphasized and they became pivotal to storylines as the series went on. Gomer went from goofy to saintly. He was now, in effect, a hick Jesus.

The goofy character who is a constant irritant to the gruff character is a template that has continued on through many successful television series, including

The Odd Couple,

Too Close for Comfort and

Family Matters.

Modern comedians, including Adam Sandler, Will Ferrell and Jim Carey, specialize in acting stupid. Not content to be perceived as plain, run-of-the-mill stupid, these comedians do everything they can to present themselves as hopelessly and peerlessly stupid. Lloyd Christmas, the character that Carey plays in

Dumb and Dumber, takes the fool's step off a steep vertical drop without the fortuitous hay wagon to break his fall.

An exception in Carey's oeuvre is the comedian's most famous character, Ace Ventura, who proves to be a rather shrewd detective.

I personally find Ventura to be funnier than Christmas.

Ferrell works in parody mode. He is comparable to Don Adams, who got laughs by parodying super spy James Bond in the modest guise of Maxwell Smart. The joke was, of course, that Smart was anything but smart. But a satirical hero like Smart was dumb in direct contrast to the clever and efficient character that he was put forth to spoof. A parody character has no real substance. It is a funhouse mirror reflection. It is a shadow that bends and stretches to exaggerate the figure from which it is cast.

A dumb spy in What's Up, Tiger Lily? (1966)

Any crisis or redemption in a Ferrell film is nothing more than a spoof of the type of crisis and redemption that can be found in a conventional film. Ferrell's

Anchorman and

Talladega Nights are, in this way, post-modern comedy films. But storytelling that is approached in a tongue-in-cheek manner is not storytelling at all.

Comedy is about the nature and condition of man. It is, in this way, the story of our lives. Philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset once wrote, "Living is a constant process of deciding what we are going to do.” We make our decisions based on our perceptions, our feelings and our thoughts, and it is through these decisions that we construct our story. The story may be a tragedy or it may be a comedy. It may reveal triumph or failure. But our story, no matter what it is, has to do with a lot more than our IQ. Comedy, in its richest form, is not about stupidity. It is about the many unique features that make us human. And what the greatest comedians have taught us is that being human is being foolish and, of course, funny.

Gag and routine note The "torn trousers" routine turns up in the

Gomer Pyle episode "Friendly Freddy, The Gentleman Tailor" (1968).

Additional Notes Characters that appear stupid may not be stupid at all.

Blackadder Rides Again (2008)

A stupid person will see a sign that explicitly says "Do not open this door" and he will open the door anyway.

The Brink's Job (1978)

Here are further dumb antics from Dumb and Dumber (1994).

Reference noteIt is worth reading Chain of Fools, which was referenced in this article. The book can be purchased at

http://www.amazon.com/Chain-Fools-Legacies-Nickelodeons-YouTube/dp/1593932405.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

_01.jpg)

.jpg)

_NRFPT_01.jpg)

_01.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)