Today, let us examine a number of early European film comedies. A fine tutorial on this subject is provided by Richard Abel's

The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema, 1896-1914, which has served as the main reference source for this article.

Reverse motion effects were used to comic effect in many early films. An ideal example is the 1903 Pathé Frères comedy

A Painter's Misfortune (released originally in France under the title

Les Mésaventures d'unartiste). The film has no real plot. A painter is busy painting a picture beside a river when, suddenly, a gang of troublemakers sneak up behind him and shove him into the water. Reverse motion causes the painter to unexpectedly rise out of the water and fall back into the clutches of villains, who merrily repeat their grabbing and jostling. This action reoccurs a number of times in an effort to elicit increasing laughs.

A surreal gag punctuates a 1910 Gaumont comedy

Mind the Wasps! (released originally in France under the title

La Guêpe). Again, the film has a simple plot. A man sitting at a sidewalk café table is suddenly bothered by a wasp. While flailing to kill the wasp, he manages to overturn tables, chairs, and a billiard table. When the wasp takes a swim in a glass of beer, the man figures to be finally rid of the wasp by consuming the beer and swallowing the pest along with the frothy brew. He smiles as soon as he empties the glass. But then he is overcome by a sickening feeling. As a crowd gathers around him, he goes into a contorted cakewalk dance, his stomach bulges and, finally, he regurgitates a fully formed wasps' nest.

Filmmakers of the day found creative ways to justify a chase. Abel provided the following description of

Rembrandt de la rue Lepic (1911):

[A]n artist sells a 'genuine' Rembrandt to a man in a crowded restaurant, a woman accidentally sits on it, the painted image transfers to her white dress, and the man rudely tries to reclaim his purchase. The woman will have none of this, of course, and a fight breaks out, clearing the restaurant and spilling out into the street. The ensuing chase, once enlivened by fast motion, destroys one social space after another — including a petit-bourgeois dining room, a garret bedroom, and a bourgeois drawing room (hosting a private concert) — and ends with the women rolled up in the canvas awning of a grocery shop. . . Despite getting his money back at the artist's studio, the obsessed buyer still cuts the 'painting' out of the exhausted woman's backside as his rightful possession.

Abel discussed an unidentified Gaumont film that was most likely produced in 1910. The plot was certainly peculiar. Abel wrote, "[The film] probably would have offended American viewers with its wildly inventive parody of Paris newlyweds who fall into a sewer, live in harmony with rats, use the carcass of a dead dog to divert a flood of water, and pop out of a gutter opening, one year later, with no less than four kids!"

In

Les Trois Willy (1913), a married couple makes plans to bring their son to meet his grandfather for the first time. But the grandfather, who is unwavering in his belief that a married couple should have at least three children, will not consent to the visit. The couple figures to make the grandfather happy by pretending to have three sons. They tell the grandfather that, to avoid tiring him, they will send the sons to visit him one at a time. They rely on their clever son, Willy, to pretend to be three separate children: a rude brat, a haughty boy wearing a monocle, and a sweet-natured boy who shows up with a bouquet of flowers.

An absurd modern fable is to be found in

Onésime and his donkey (released originally in France under the title

Onésime et son âne). The film is described by Abel as follows:

Onésime [Ernest Bourbon] has promised his only companion, an ass named Aliboron, that he will share any wealth he comes to possess. One day, in a variation on the féerie fable of the hen that laid the golden egg, the ass literally begins to shit golden coins. As promised, the comic treats Aliboron royally — after all, as a piece of property, the ass has turned into a rentier's 'dream machine.' Indeed, the comic himself now turns into a servant in a series of repeated gags — bathing and dressing Aliboron, serving him dinner in a restaurant, putting him to sleep in a proper bed . . . [I]n the end, the coins prove to be fake, and Onésime reverts to his former state, except for the reversed master-servant relationship that the ass has 'earned' and to which he has grown accustomed. The film's final [shot] has Onésime, still a 'slave' to his property, now pulling Aliboron comfortably seated in a cart.

Suicide comedies were commonplace during this period. These comedies could get extremely silly in spite of their grave premise. Let's take, for example, the 1911 Pathé Frères comedy

Rigadin's Nose (released originally in France under the title

Le Nez de Rigadin). This film, as others in this genre, reminds us that love brings heartbreak more often than joy. Rigadin (Charles Prince) is harshly rejected by a woman due to his large, upturned nose. He tries to fool the woman by wearing a fake nose, but a dog snatches the prosthetic proboscis off his face. Dejected, Rigadin attempts to hang himself, but the noose gets caught on his nose.

More involved is the 1912 Gaumont comedy

Onésime et le chien bienfaisant (the translation of which is

Onésime and the benevolent dog). Onésime (Bourbon) has fallen in love with a pretty young woman, but the woman has been promised by her father to another man. Onésime, according to Abel, "plunges. . . into a funk." He sees no other option other than to kill himself. Abel wrote, "The father's big black poodle is dismayed at the choice, however, and determines to rectify this situation. First, the poodle saves Onésime from asphyxiating himself — it jumps in one of his windows and carries off several smoking logs." Later, the poodle fetches a woman's undergarment and delivers it to the rival's bedroom to make it look to the father as if the man is having an illicit affair.

Man's enduring hostility towards mothers-in-law is at the basis of the 1912 comedy

Alone at Last (released originally in France as

Finalmente soli!). Ernesto Vaser is fed up with an interfering mother-in-law who has joined him and his bride on their honeymoon and has insisted on sleeping between the couple in the marital bed. Vaser finally disposes of the woman by setting her aloft in a large helium balloon.

Another man feels ill will towards his mother-in-law in the 1911 Pathé Frères comedy

Jobard a tué sa belle-mère. Lucien Cazalis dresses up as a ghost to scare his mother-in-law. When the woman faints, Cazalis fears that he has killed her. The film must have been a success because Cazalis later reworked the premise for

Le crime de Caza (1915, Pathé Frères). Harold Lloyd used the same premise several years later in

Hot Water (1924). Lloyd soaks his mother-in-law's handkerchief in chloroform to put the irritating woman into a sound sleep for the evening. However, he panics when it appears that the chloroform has put the woman into a permanent sleep.

Yet another disgruntled son-in-law turns up in the 1910 Pathé Frères comedy

The Crocodile (released originally in France under the title

Le Caïman). The film opens with a husband visiting a shipping office to claim a crocodile that has arrived from Egypt. The man has concocted a scheme to have the crocodile devour his mother-in-law, ridding him of this bane of his existence. Abel wrote, "[F]reed from its crate, the animal cordially seals their agreement with a handshake." Back at the apartment, the husband sends the crocodile into the mother-in-law's bedroom, where it slips under her bedcovers. The woman's flailing feet suggest that she is being eaten alive. But the husband feels guilty when his wife expresses concern about her mother's whereabouts. He fires a revolver at the crocodile, after which he slices open the animal's stomach and pulls out his mother-in-law alive and intact.

André Deed performs an early version of the "bridal run" routine in

Cretinetti troppo bello (1909, Itala). Unique to this variation of the routine is the surreal and macabre ending.

Various emotional states are explored in a 1911 comedy called

Foolshead's Christmas (released originally in Italy as

Il Natale di Cretinetti). Deed bumps into a postman while rushing home with Christmas packages. He drops the packages and accidentally picks up a packet containing three bottles of ether. At home, Deed accidentally breaks the bottles one by one. The gaseous mixtures have the strange effect of changing the mood of the home's occupants from fearful to happy to angry.

![]() |

| Cretinetti in the cinema (1911) |

In

Le Negre blanc (1910), Charles Prince plays a black man who has fallen in love with a white woman. Knowing that neither the woman nor her father will accept him due to his skin color, he seeks out a coloring expert to lighten his skin. The coloring expert gives his anxious patient a special concoction to drink. Prince starts out drinking half the mixture, which turns half his face white, and then he drinks the rest of the mixture to complete the effect. Upset to learn that the young woman has consented to marry another man, Prince slips the skin-coloring concoction into the woman's champagne glass and proposes that they toast to her engagement. The woman no sooner drinks the champagne then she becomes black. At this point, she is promptly rejected by her fiancé, who storms out of the home in disgust. The woman is also rejected by her own father and even Prince, who finds himself so loath to associate with a dark-skinned lady that he haughtily turns on his heels and departs the premises.

Anxiety about interracial romance reached a bizarre peak in the 1911 comedy

An Odd Adventure of Foolshead (released originally in France under the title

Una strana avventura di Cretinetti). A large black woman (a white man in drag and blackface) takes a romantic interest in Deed. She chases her reluctant lover through the city with a bow and arrow. After much destruction occurs in her desperate pursuit, she finally manages to take Deed captive. An intertitle indicates that three years have passed. Deed and the woman are now surrounded by several children who are half white on one side and half black on the other.

Max pédicure (1914) features Max Linder as a bourgeois dandy interested in having an affair with a married woman (Lucy d'Orbel). When he calls on the woman, he is startled by the sudden arrival of the woman's husband. Abel wrote, "Max goes into a panic, racing around the room like a caged animal . . ." Max assumes the guise of a pedicurist who has arrived at the home for a scheduled appointment. When the husband enters, Max is busy working a tiny file on the woman's toenails. The situation takes a turn for the worse when the husband requests that Max give him a pedicure. Max dons gloves so that he doesn't have to make direct contact with the man's feet, but this does not make his job any less disagreeable. He becomes nauseous as he cautiously works at getting off the man's dirty socks. The comedian uses his extraordinary expressiveness as an actor to make the most of this scene.

![]()

Linder was successful at elaborating on other filmmakers' ideas. Audiences of the day were amused by the simple plot of the 1907 Pathé Frères comedy

Spot on the Phone (released originally in France under the title

Médor au téléphone). Abel described the plot as follows: "[A] man goes to have a drink at a sidewalk café, realizes he has left his dog at home, and calls the dog on the telephone to tell it where to find him." The dog is shown perched atop a high stool so that it can bark into the phone. Linder expanded on this premise in a 1912 comedy

Max and Dog Dick (released originally in France under the title

Max et son chien Dick). This time, the dog phones its master to alert him that his wife has brought a lover into their home.

A popular music hall comedian, Félix Galipaux, was well-known for a routine in which he pretended to be an adolescent who smokes his first cigar. This pantomime routine was ideal for silent films. Galipaux performed the routine on camera for a 1903 comedy,

Cadet's First Smoke (released originally in France under the title

Premier Cigare du collégien). The film was described in the Edison Catalog as follows: "[A cadet] starts to smoke his first cigar. He begins with a smile of contentment and many ludicrous facial expressions, but after proceeding a short time with his smoke his nerves begin to forsake him. A pained expression passes over his face and he begins to perspire. Then he becomes deathly ill. The facial contortions that follow keep the audience in continued laughter." Linder recreated the routine in

Le Premier Cigare d'un collégien (1908). Abel wrote, "[Linder is] puffing on the cigar and smiling and then looking at it strangely; puffing again, frowning, and looking a bit ill; puffing a third time, belching, and, with his eyes suddenly bulging, holding a handkerchief to his mouth." See the film for yourself.

William Sanders performed the routine in a 1911 Éclair comedy,

Willie's First Cigar (originally released in France under the title

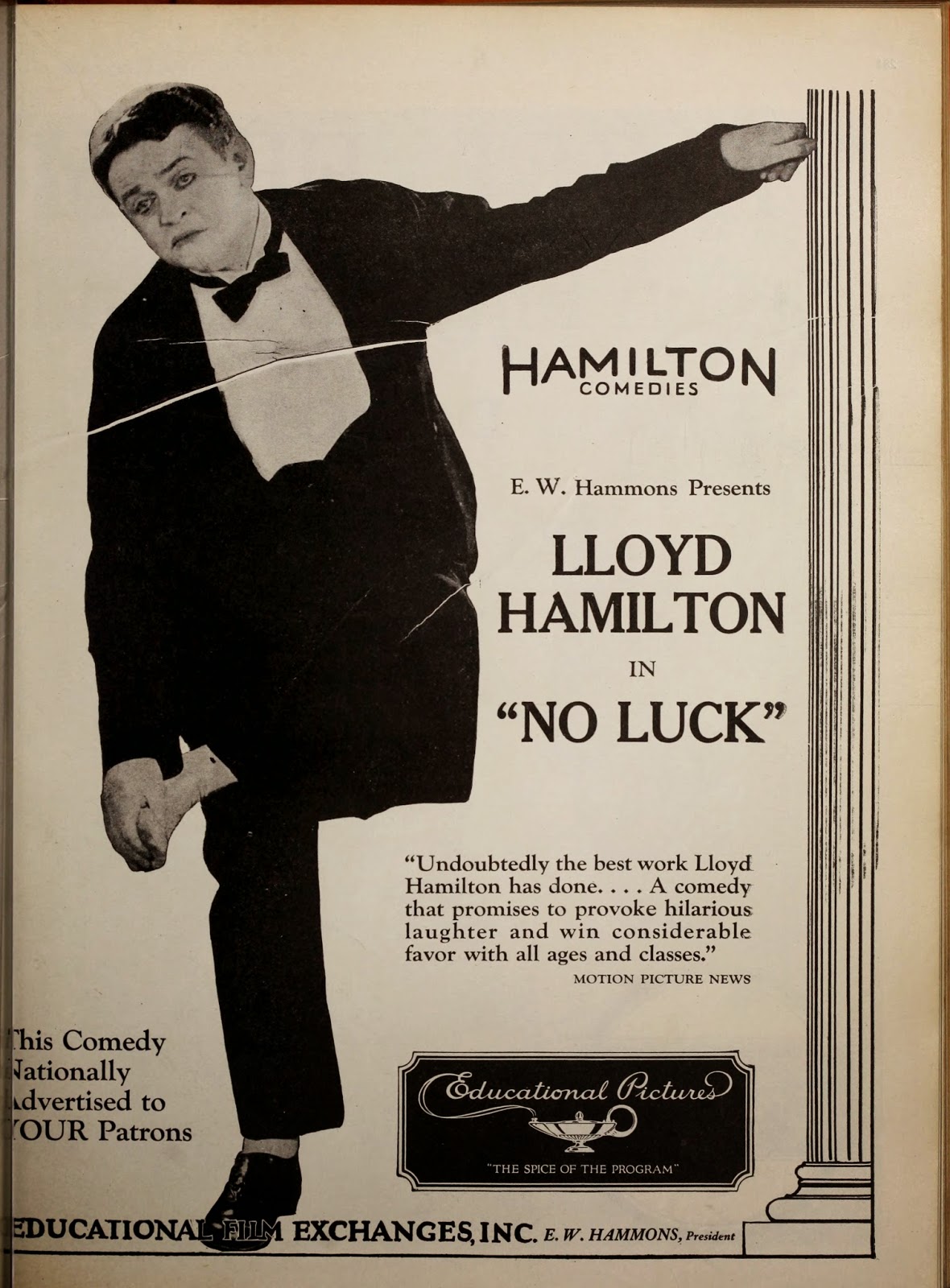

Le premier cigare de Willy). Lloyd Hamilton performed the routine in

No Luck (1923). In this instance, the film speed slows to suggest the dulling effect that the cigar has on Hamilton's mental facilities. This was an ideal routine for Hamilton, who chiefly derived humor from his distinct reactions. A simple scene that allowed the comedian to get laughs with nothing more than facial expressions generally drew praise from critics. Take, for example, a scene from

The Educator (1922). Hamilton contorts his face and rolls his eyes as he struggles to brush aside a persistent fly that has landed on his nose. In Exhibitors Trade Review, a critic devoted the entire first paragraph of his review to an extensive discussion of this scene.

Every action builds to a silly payoff gag in the 1910 Gaumont comedy

Jiggers Buys a Watch Dog (released originally in France under the title

Calino achête un chien de garde). Gaumont's resident boob, Calino (Clément Mégé), discovers his home has been ransacked by robbers. This motivates him to purchase a ferocious watchdog. The household — husband, wife, butler, maid, and gardener — prepare for the dog's arrival by constructing an immense doghouse and nailing up a "Danger" sign. Abel wrote, "At the kennel, Calino chooses the largest, nastiest beast available — it takes two men to wrestle it into a crate on a cart — but fails to tip one of the dog handlers. . ." The disgruntled dog handler vows to take revenge. The crate is later delivered to Calino's home. His family is fearfully trembling in anticipation of meeting the beastly dog. The group is, however, prepared for the worse. They are, according to Abel, "dressed in odd bits of armor [and] clasping guns." Calino opens the crate and tugs on a large chain. Finally emerging from the crate is a tiny, harmless dog.

Deed's influence was evident in the mass destruction that often occurred in the "Calino" series. In

Calino apeur du feu (1910), a haggard old fortuneteller warns Calino that, unless he is careful, he is going to perish by fire. Frightened, Calino immediately tosses his cigarette into the gutter and stamps his foot down on it. Then, he straps a huge fire extinguisher on his back and strolls through the city spraying water at people smoking cigarettes and automobiles belching exhaust fumes. The film climaxes with Calino climbing a townhouse roof to extinguish a series of smoking chimneys. Abel wrote, "An extended sequence follows, alternating between the rooftop, the townhouse dining room (where water pours out of a fireplace to soak a bourgeois couple), the adjacent kitchen (where water erupts out of the stove and splashes the maid), and finally the street below (where two smoking policemen are hit by a cascade of water)." After Calino is finally arrested, the film still has one last gag to offer. Abel wrote, "[A]s the police chief lights a cigarette, Calino goes into a quaking fit and then sprays him, too, with his seemingly inexhaustible extinguisher." The film was remade in 1913 as

Fricot and the fire extinguisher (released originally in Italy under the title

Fricot e l'estintore).

This is a poster for

Calino sourcier (1913).

Abel summarized the film's plot as follows: "Calino is equipped with a divining rod that makes water spring out of the most unlikely places. When he is arrested and taken off to the police station, the rod promptly causes jets of water to erupt out of a wall painting, a desk inkwell, and even one cop's ear. In a clever twist at the end, Calino himself magically dissolves away in a jail cell, leaving water spraying from every direction."

These films were wonderfully surreal and satirical. The comedians who later achieved success in silent films were in one way or another influenced by the early work of these European comedians, including Max Linder, André Deed, Clément Mégé, Ernest Bourbon, Marcel Perez,

and Charles Prince.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.gif)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

a.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2B-%2Bcineaprju04gdur_0172b.jpg)